Q: “Misplaced Childhood” captures a very specific and poignant contradiction: children engaged in play while simultaneously bearing the weight of adult responsibilities. What drew you, personally, to explore this theme in rural Poland?

To be honest, we often spend time in Pashin — a village near Nowy Sącz, where my partner Kasia’s parents live. Every visit confronts me with a very particular world — the atmosphere of contemporary rural Poland. This world is not foreign to me; on the contrary, it draws me in and makes me want to look closer. In conversations with Kasia, we came to the conclusion that this environment holds enormous potential for artistic exploration, especially within documentary photography. It allows me to step into the role of a researcher armed with a camera, documenting the everyday manifestations and unique aspects of this microcosm.

At the same time, this world resonates with me on a cultural level: despite the difficult history, Polish and Ukrainian mentalities have much in common. I am convinced that in any art form, authenticity is the most essential element. Projects that we truly live through, that awaken compassion and empathy, possess a special power. They are self-sufficient, impossible to confuse with artificial constructs or “pseudo-reflections.” If an artist is not genuinely engaged with their subject, the work lacks depth.

Coming back to Misplaced Childhood: this is the first project that Kasia (Katarzyna Bochenek) and I began to develop together, exploring the micro-world of the Sądecki region and the village of Pashin. What first struck me was the unusual sight of children freely riding motorcycles around the village. The very first image, Young Rider, was made in 2022, when I photographed Kasia’s nephew Kuba on his cross bike. Later, the series expanded, and one of the key images became a group portrait of Kasia’s younger son, Jędrzej, together with his two cousins, Kuba and Max. This was the beginning of the project’s narrative.

In the countryside, children are drawn into adult life much earlier: they help parents with daily responsibilities, they take on duties. Their childhood is very different from the “protected” version that many urban parents try to create for their kids by shielding them from obligations. But early maturity almost always comes with a loss of carefree innocence. Even while still children, their space of responsibility expands.

This theme is deeply personal to me. I grew up in the 1990s with my brother Viktor — a very difficult time for the countries of the former Soviet Union. In many ways, we were raised by the street: our parents, despite their cultural heritage, were focused on survival, and they didn’t always have the strength to be present. This forced maturity, this premature adulthood shaped by harsh economic realities, is a painful but familiar experience to me. And it is precisely this that lies at the core of Misplaced Childhood.

Q: As you developed the distinct visual language for this series, which documentary photographers or filmmakers influenced your perspective?

If you perceive a distinct visual language in this series, for me that already feels like a form of recognition. I draw an important distinction between style and artistic language. Style is often about form and its limitations, while language speaks to content — and form becomes an expression of that content. I would like to believe that I am gradually moving closer to my own artistic language.

I cannot say that I am deeply familiar with the tradition of documentary photographers, and my perception does not directly stem from them. A powerful impression on me came from Jeff Wall’s exhibition at the PinchukArtCentre in Kyiv in 2012. His work can hardly be classified as purely documentary photography, but it was revelatory to me. The states of the people in his images I would describe as raw — stripped of superficial emotions yet filled with a profound inner depth.

In cinema, the work of Andrei Tarkovsky holds a special place in my perception. His films are imbued with an existential, even transcendent quality, and this resonates very strongly with my worldview.

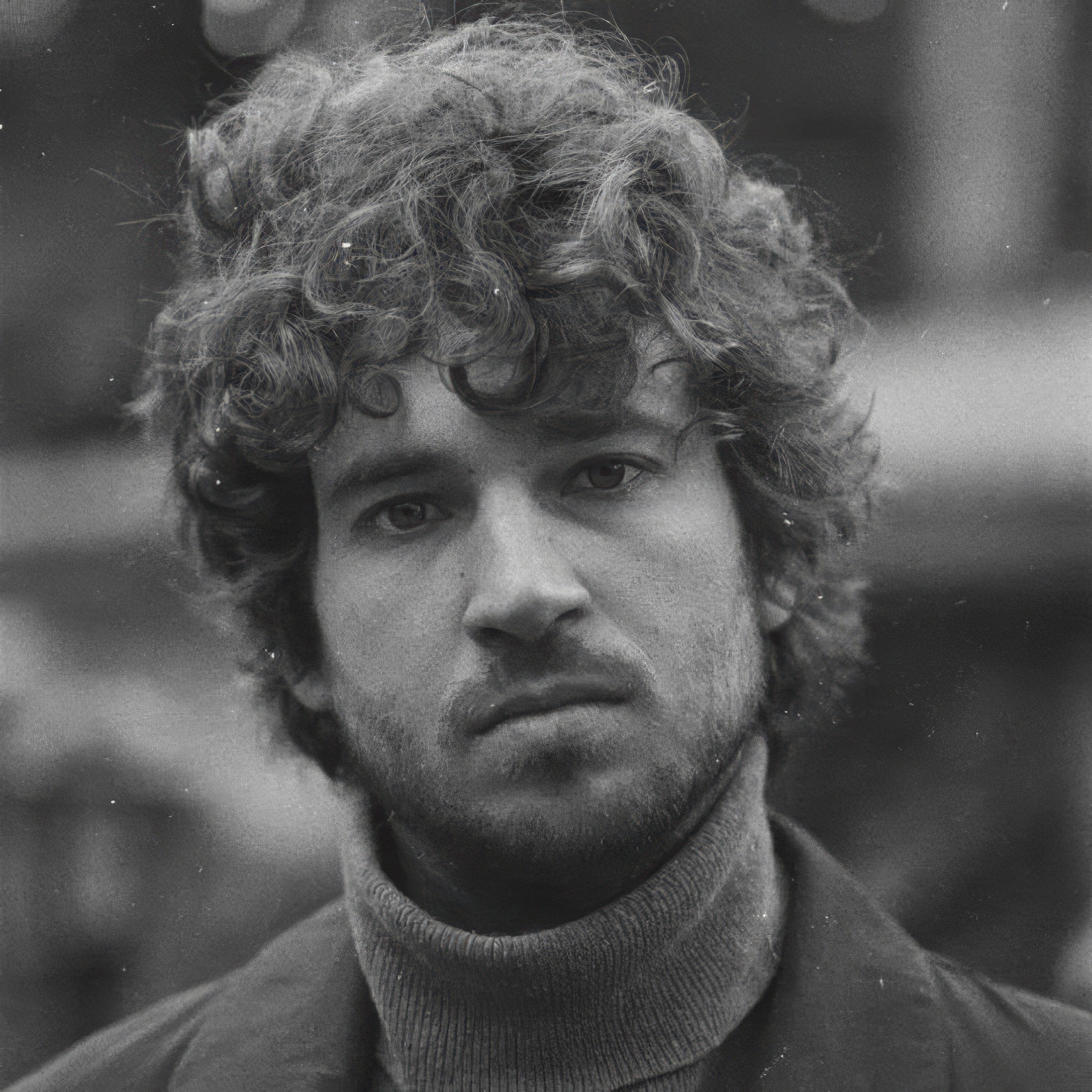

When I look at my own portraits, I increasingly notice that the central composition and the way I aim to reveal the human presence often stem, on a subconscious level, from my admiration for icon painting. The works of Theophanes the Greek and Andrei Rublev inspire me not only aesthetically but also through their theology — the concept of the icon as a window into another reality.

Q: What motivated the decision to use analog black-and-white film to express the project’s themes of timelessness and emotional authenticity? Was this aesthetic direction part of your initial vision?

In general, black-and-white film photography holds a very special place in my practice. To put it the other way around — I mostly use digital cameras for commercial projects, but very rarely for artistic ones. The commercial market demands speed and efficiency: digital photography allows us to multiply images endlessly, reducing the risk of technical error and lowering the responsibility for each single frame. It is convenient, flexible, fast — but often at the cost of diminishing the very value of the photograph itself.

Film, on the other hand, requires a completely different approach: thoughtfulness, focus, deliberation. This is especially true with large format, where the number of frames is limited, exposure has to be calculated carefully, and focus is often achieved manually. There is little room for mistakes — but in return you gain what I call material authenticity: the physical existence of the negative as an object.

With Misplaced Childhood, this was not an aesthetic decision made specifically for the project. All of my significant work I create on film, most often in black and white. For this, I am particularly grateful to my teacher, Ata Ovezgeldyyev, who years ago helped me find direction in my practice: portraiture, black-and-white, film.

Beyond that, film itself carries what I call emotional authenticity. The grain, the texture, the physicality of negatives and prints — they add another layer of reality to the image. I am convinced that without film, this series would not have the strength or the honesty I am striving for.

Q: Can you describe your process for connecting with the children and their families in these communities? How did you approach making them comfortable in front of the camera to capture such natural and revealing moments?

I never had to artificially build relationships with these families and their children. They are all, in one way or another, relatives of my partner Kasia — some closer, some more distant. By creating our own family together, I naturally became part of hers, just as she became part of mine. So the process of getting to know them and developing friendships happened organically, and at some point it felt completely natural to bring photography into this space. I began photographing them — and they, in turn, gladly became participants in my projects.

As for why they seem so comfortable, natural, and unguarded in front of the camera — perhaps it is precisely because I never tried to force it. I didn’t set myself the goal of making them “open up”; I simply observed and photographed.

Over time, I noticed a certain pattern: when a photographer is demanding first and foremost of themselves, the people in front of the camera immediately feel it. They begin to behave differently — with greater attentiveness, awareness, and seriousness. Children, in particular, are especially sensitive to atmosphere and emotional tone. For them, these photo sessions become not just a game or an episode, but a meaningful experience.

Q: Winning the title of Non-professional Analog / Film Photographer of the Year is a significant achievement. What does this recognition represent for you?

First and foremost — it is gratitude. Gratitude to my parents, Iryna and Volodymyr Lemzyakov, to my life partner and the mother of our daughter, Katarzyna Bochenek, to my life mentor Ata Ovezgeldyyev, to my teacher in photography Maciej Plewiński, to my “second parents” Sergii Malyarov and Maryna Kolyada, and to all my family and loved ones who believe in me and support me on this journey.

Secondly, it is confirmation that persistence and determination do bear fruit. It is important to follow one’s own path and never stop. Achievements like this become milestones — something to lean on and move forward from.

And finally, it is a source of inspiration for the steps ahead. I believe that our failures shape us, but it is our successes that give us wings and inspire hope.

Q: Based on your journey creating “Misplaced Childhood,” what guidance would you offer on approaching sensitive subjects with respect and building a narrative that is truthful and empowering rather than intrusive?

The question itself already contains much of the answer: it includes the words “with respect” and “narrative that is truthful.” Respect — for yourself, for what you do, for others, and for the world at large — is the foundation. Honest storytelling in photography is only possible when a person is first honest with themselves. This applies not only to art but to every form of human expression.

I believe that etiquette can be taught, but true culture is carried by people with a particular way of perceiving the world. Each of us has our own sensitivity, and while we may be inspired by others, we cannot become them. This is less about skill and more about perception.

I am convinced that relationships are always reciprocal: the way people treat us reflects the way we treat them. That is why, when I photograph, I try to remain true to myself — and then the person in front of the camera also remains true to themselves.

To sum it up: if you don’t want your project to feel intrusive, don’t be intrusive.